We often hear sports commentators talking about players being ‘in the zone’. This phrase is commonly used when a player is performing well and operating within what is known as their comfort zone. The player in the zone is focussed and their mind is on their performance. Their shots and plays are coming naturally to them and mistakes are minimised. They are thinking clearly and making the right decisions. A player who is in the zone will be performing to the best of their ability. They will also be relaxed as they undertake the task at hand and an observer would note how easy the player is making the activity look.

Contrast this to a player who is outside their comfort zone. This player will make errors they might not normally make. Often the player will be sweating heavily or exhibiting other signs of anxiety. They will seem distracted with small things upsetting them. As they struggle to perform to what they believe is their ‘normal’ level, they will become more anxious and/or upset about their performance and this anxiety will increase the tension and stress the player is feeling making it difficult for the player to relax and restore their performance to their normal level.

A comfort zone is created from one’s experiences, skill level and prior performances. As our experience and skill improves, our performances improve and our comfort zone increases. A comfort zone isn’t just based on performances or scores, but also on environmental factors. For example, a player contesting a competition on their home ground is more likely to feel relaxed and comfortable than if they are in an unfamiliar environment. A bridge player who is used to playing at their local club and who suddenly finds themselves playing on vu-graph or with a kibitzer at the table in a national event might feel out of their comfort zone. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the player will perform below their best since we have all seen examples of less experienced players winning against their more seasoned opponents in all types of activities. It does mean that when a player is outside their comfort zone, they are more likely to make errors they wouldn’t make when they are in a more familiar or comfortable environment.

Why does performance drop when a player is outside their comfort zone?

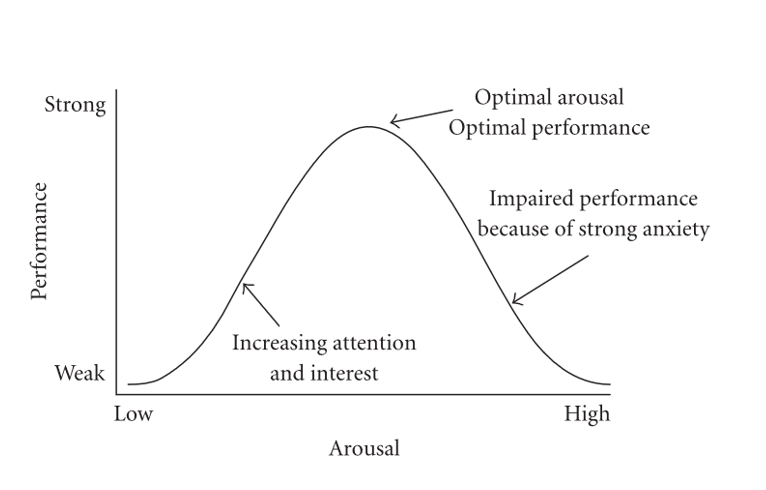

The reason is described by Yerkes-Dodson law, the Hebbian version of which is depicted in the chart shown below. (Note: Interested readers can google Yerkes-Dodson for further detailed research.)

The chart shows that some level of arousal is required for performance, however problems arise when this arousal or anxiety is too high. When this occurs performance will suffer as the overly heightened anxiety causes cognitive impairment. When a player is outside their comfort zone and suffering from this increased arousal or anxiety they will be more likely to make errors.

At a recent matchpoint event my less experienced partner remarked to me that the field at the event was ‘really tough’. While it is important to respect your opponents, it is also clear that voicing a view that the field is strong or tough isn’t helpful to your confidence, and could be seen as indicating you feel out of your comfort zone. If for example my partner had said instead – “this is a tough field but there is no-one in it that we can’t beat”, it would have demonstrated that my partner was within his comfort zone and likely to perform to normal standards.

With this comment indicating slightly increased anxiety the following hand came up in the first round of the event North-South reached a routine 3NT after South opened 1NT and North raised to three. North-South can make ten tricks on normal play. Partner holding the West hand led the queen of spades with East playing an encouraging three (reverse attitude) and declarer winning in hand with the ace. Declarer exited a low diamond towards dummy’s queen which West ducked and declarer continued diamonds with West winning the third round while East pitched a high heart (discouraging). West has a clear option to continue spades which East had encouraged. Instead West made the unusual choice of switching to a low club which Declarer ran around to the queen. Declarer could finesse West’s king and claim twelve tricks for a top board for the opponents. A club exit cannot be right since even if East has the queen of clubs it will always win when declarer takes the finesse and it is more important to knock out declarer’s last spade stopper.

Dealer: South

Vulnerable: E – W

♠ QJ974

♥ J6

♦ A65

♣ K94

♠ K5

♥ K105

♦ QJ73

♣ AJ87

♠ A2

♥ AQ7

♦ K842

♣ Q653

♠ 10863

♥ 98732

♦ 109

♣ 102

This does not seem a particularly tricky defence, yet West who had earlier expressed concern regarding the field quality might have been feeling stressed or anxious and hence made a simple error in defence. We have all seen players make simple errors when they are feeling the pressure. On another day in a different field, my partner would most likely have got the defence right every time.

How can we lift our ‘comfort zone’ to increase the likelihood of success?

Unfortunately, there is no magic fix but understanding what is going on is a great start to a solution. Lifting your comfort zone requires hard work and development over time. A number of elements are involved and each must be addressed so that the player can continue to perform when under pressure. These elements include:

- Technical ability in card play. For example, learning by rote how to play basic card combinations; automatically counting out the hand when dummy comes down or after the opening lead is made; and so on.

- Have simple system agreements and general principles that can be easily remembered and apply in many auctions to reduce the likelihood of errors when under pressure.

- Increase your exposure to being outside your comfort zone. It’s fair to say that the more frequently a player reaches the finals, or plays in more difficult or competitive situations, the more likely they are to “break through” and win. Putting oneself in pressure situations by playing against stronger players, playing in a more competitive field, moving from the ‘weak’ side to the ‘strong’ side at your club, playing in open rather than restricted events, and even having friends come to watch you play will assist with improving your comfort zone.

- Learn to relax at the table. A few deep breaths go a long way to helping to release tension when you are feeling under pressure.

- Imagining yourself in situations outside your comfort zone is also helpful. For example, picturing yourself playing on vu-graph or behind screens before you have to do it will help you be prepared for the real thing. This is commonly known as visualisation in the sporting world and a future article in this series will focus on visualisation and how it can assist your performance.

The most important thing of all however, is believing you are good enough to win.

© First published in Australian Bridge. February 2019.