I had planned to contest the Asia Pacific Bridge Federation Championships, which were to be held in Perth in April 2020. Everything was booked. Without warning, my plans were thrown into disarray because of a little bug which has created a world-wide crisis – Covid-19. The disruption to my plans pales somewhat when compared with some of my bridge friends who had achieved selection to contest the World Championships in Salsomaggiore, Italy in August – for some this was their first time on a team. How disappointed they must be. It also pales compared with Olympians who have trained for years to achieve selection for an event that comes around once every four years.

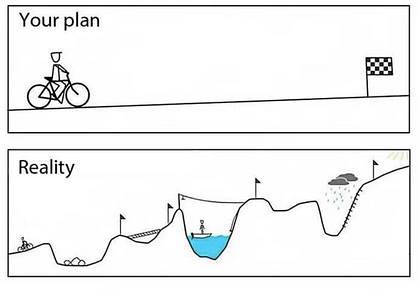

There is no doubt in my mind that missing a chance to play in ‘the Worlds’ or the Olympics is devastating – after all. who knows whether the opportunity will still be there in a year’s time? Injury, illness or age may preclude participation at a future time. However, assume everything is just postponed for a year or so. The challenge for us then, is how do we take this disruption and use it as an opportunity to come out the other side as stronger players. One of our top Australian Olympians spoke about how this enforced break created an opportunity for her to recover from all the niggling injuries that often plague top level sportspeople.

How can we as bridge players turn this into an opportunity? In my sporting days, I used the off-season to make changes to equipment or technique when there were no important competitions coming up. The enforced shutdown for bridge is clearly the equivalent of the sporting ‘off-season’. Taking advantage of this forced break from competition to work on aspects of your bridge which you might have been putting off for some time is an opportunity too good to pass up. For me, this has involved working on incorporating more relays into our system. My partner has wanted us to include them for some time, but I have never found the time to really work on and become comfortable with them. The theory behind our change is that the new method will be better for bidding in the slam zone.

Why is slam bidding so important when slams come up so infrequently?

Aside from the fact that at tournaments no one ever seems to ask if you won a partscore on Board 3, but they do ask ‘did you bid the slam?’ or ‘did you bid the grand?’. The number of IMPs which can be won or lost by effective slam bidding in high level bridge is quite astounding. This fact was well made in a report I read a few years ago on one of our international team’s results. It highlighted just how many IMPs were won or lost in this area by the team. It goes without saying that a 10+ IMP swing for getting each slam auction correct is crucial.

The following hand is one we played in the 2019 Butler Pairs at the Australian National Championships, which features many of our top pairs. For us, it came up towards the end of the two-day qualifying event and using our old methods, we easily reached 6NT along with most of the field. A small number, however, (7 out of 43) reached the grand slam in diamonds or notrumps.

Dealer: South

Vulnerable EW

♠ J1097

♥ 10986

♦ J

♣ 832

♠ KQ532

♥ –

♦ K109874

♣ A10

♠ A6

♥ AKJ754

♦ AQ

♣ KJ4

♠ 84

♥ Q32

♦ 6532

♣ Q975

Old Method (EW passing throughout)

South North

2♣ 3♦1

3♥2 3♠3

4♦4 4NT5

5♠6 6♥7

6NT

1 – Positive 8+; 5+ diamonds

2 – Natural

3 – Natural

4 – Keycard on diamonds

5 – 2 Keycards, no queen of trumps

6 – Ask in Spades

7 – Ace or king & queen

It is easy to say that South should have deduced 13 tricks were possible or that North’s three diamond bid ought to promise six diamonds and any possible club loser might be pitched on the king of hearts. But normally when one bids a grand slam, we like to have reasonable assurance that 13 tricks will be made. Looking at it now – I can see about 15 tricks! Clearly a lot of the well-credentialed pairs in the field also had problems reaching the grand slam, no matter what method they were using. It can also be difficult to draw the correct inferences about your partner’s hand when under pressure at the table, or when tiring towards the end of the day. Knowing precisely what is shown utilising our new method with relays will bring more certainty to our decision-making.

With this method it was easy to find out about North’s 6-5 shape, and then to count 13 tricks. (We assume that the jack of diamonds would fall in three rounds.)

South North

1♣1 2♣2

2♦3 3♦4

3♠5 3NT6

4♣7 4♠8

5♠9 6♥10

7NT11

1 – 11+ any shape not in our other opening bids

2 – 5+ diamonds; 13+ points

3 – relay

4 – 6+ diamonds & 5+ spades

5 – Range keycard ask in diamonds

6 – minimum

7 – Keycard ask in diamonds (tell me anyway)

8 – Two keycards, no queen of trumps

9 – Ask in spades

10 – Ace of spades or king & queen of spades

11- I can count 13

I believe the new method will give us an edge in the slam zone when we are able to return to competitive bridge at the table. Like any game, it is all those little edges that make you a more formidable opponent – it will remain to be seen if all the work during shutdown has been worth it.

First published: Australian Bridge, June 2020